projects

DUNDEE: THE VERDANT WORKS

The full restoration and installation of a Boulton and Watt Rotative Beam Engine

In early 2015, Lost Art Limited were engaged on a project of immense heritage value as we were selected to undertake the restoration of the Boulton and Watt Rotative Beam Engine located at the Verdant Works Museum in Dundee. Given the nature of the engine (there is another example in the Energy Hall of the Science Museum in London) and the location of the engine in James Watt’s home country, this is an historic artefact of both national and international significance and one that we were both pleased and excited to have been contracted to undertake. The recommendation that Lost Art be appointed for the project came following our successful involvement in the restoration of a Newcomen type beam engine at the Elsecar Heritage Site – as also described within our web page.

The engine itself is a magnificent example of a Boulton and Watt Beam Engine, featuring historically and developmentally significant features such as a separate condenser, sun and planet gear movements, parallel motion and centrifugal governor – which even if the terms are not familiar to you – are extremely impressive when viewed in action.

The engine was originally installed at the DouglasfieldBleachworks in 1802 at a cost of just over £500 and was then worked for almost 100 years before being donated to and installed in a museum at Dudhope Barracks. This museum never re-opened after World War II and the engine was dismantled during the 1960s and although intended for display in Edinburgh, this never came to fruition and the engine was returned to Dundee in 1975, where it remained in storage until the present project was initiated.

The engine was collected by Lost Art in approximately 200 pieces and transported back to our workshop. The pieces ranged in size from the magnificent oak beam and impressively large gear wheels to a selection of the original nuts and bolts. However, analysis at the workshop revealed that several components were missing and would have to be produced by Lost Art but also there were items that were present that did not belong to the engine and would have to be identified and excluded.

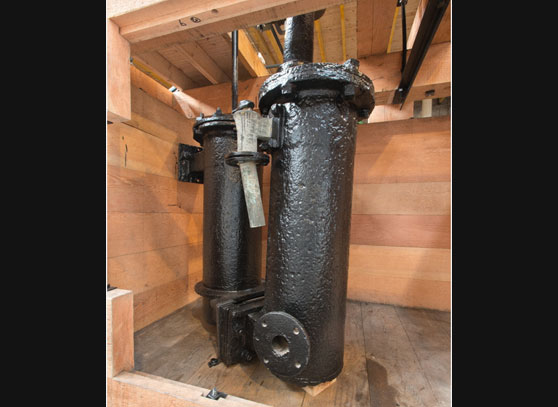

Once all the remaining components had been fully cleaned and their condition assessed, the initial assembly of the largest jigsaw that any of us had worked on began to take place – there were historical images of the full engine available but these dated back many decades and there were no plans left in existence. Working on sub-assemblies of the engine allowed us to identify which missing elements would require hand production by our craftspeople and which would require the creation of a pattern and then production in cast-iron at the foundry. An example of these being the components known as strongbacks – the type shown below were fitted to the enginein order to strengthen, spread the load and stresses and so provide protection for the rocking beam.

Nuts, bolts, an arm for the governor balls and straps for the frame assembly were included in the items produced in the workshop. In keeping with the best conservation principles, all newly produced items included in the restoration carried markings identifying them as such.

Reassembly in the museum required time, patience and not an inconsiderable amount of skill – especially in the movement and placing of large items by crane, with tolerances and gaps of very few centimetres (or inches as they would have been at the time of the original construction).

The final display of the engine in its new location has gathered great praise from a number of highly respected sources and we are rather proud of it, if the truth be known.